January 16, 2016

The Big Sleep: the Rational Suicide of Melbourne Scientists Pat & Peter Shaw

Sydney Morning Herald by Julia Medew

Scientists Pat and Peter Shaw died in a suicide pact in October.

Here, their daughters reflect on their parents’ plan – and their remarkable lives.

For as long as the blue-eyed Shaw sisters can remember, they knew that their parents planned to one day take their own lives.

It was often a topic of conversation. Patricia and Peter Shaw would discuss with their three daughters their determination to avoid hospitals, nursing homes, palliative care units – any institution that would threaten their independence in old age.

Having watched siblings and elderly friends decline, Pat and Peter spoke of their desire to choose the time and manner of their deaths.

To this end, the couple, from the Melbourne bayside suburb of Brighton, became members of Exit International, the pro-euthanasia group run by Philip Nitschke that teaches people peaceful methods to end their own lives.

The family had a good line in black humour. The three sisters recall telephone conversations with their mother in which she would joke about the equipment their father had bought after attending Exit workshops. “He’s in the bedroom testing it,” Pat would quip.

About four years ago, Pat and Peter’s resolve to stay away from hospitals was heightened. While hanging washing in the backyard of their beloved home, Pat, then 83, tripped and broke a bone in her thigh. She was carted off to the emergency department. Her fracture healed well but doctors were concerned about her high blood pressure. They wanted to keep her in and treat it until it was under control.

Pat disagreed. A biochemist who had taught medical students at Monash University for decades, she blamed the medicos for driving up her blood pressure. She said she knew how to treat it and so, against dire warnings, she left the hospital with Peter. Sure enough, when she got home her blood pressure dropped within days.

The two scientists relished life. They skied, went bushwalking and climbed mountains, often taking their three young daughters with them. Their cultural and intellectual pursuits were many – classical music, opera, literature, wine, arguments over dinner with their many friends. They donated 10 per cent of their annual income to political and environmental movements. Family events were spent thoroughly debating the topics of the day.

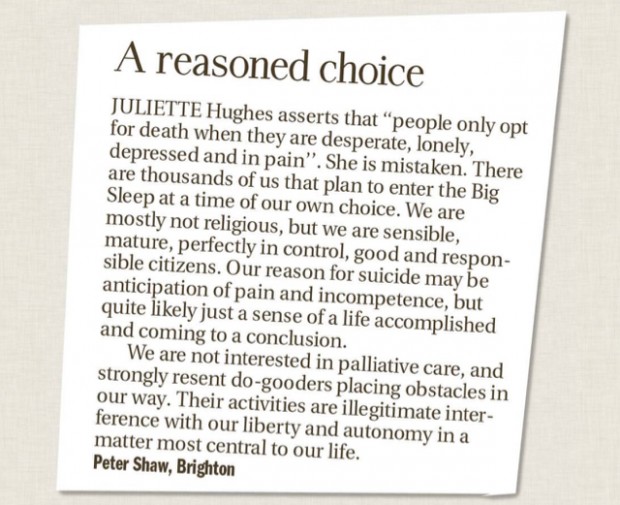

As their capacity declined, the conversation about ending their own lives became more serious and their rejection of what Peter called “religious do-gooders” became more fierce.

“It was also a way into their favourite topics; philosophy, ethics, politics, the law …,” says their youngest daughter, Kate. “The idea that their end-of-life decisions could be interfered with by people with the superstitions of medieval inquisitors astounded them, and alarmed them.”

In April, Peter, an eminent meteorologist, was labouring. He sat down at his computer and typed a letter to his daughters, three highly educated women – two have PhDs and one is a concert violinist in Germany.

“My head swims,” he wrote. “When I am reading, I can’t follow a difficult argument, so I give up, telling myself that it doesn’t matter, and I will read something else. I have just now been reading the history and politics arguments at the end of the latest Quarterly Essay and I am very disappointed that I can’t follow them.”

“My condition is getting worse bit by bit, slowly week by week. On top of all this, my eyesight and hearing are no good, my pulse is occasionally irregular. So how long can it go on? Weeks? Months? As you all know, I am not afraid of dying but I am dead scared of incompetence.”

Pat was also troubled by her old age. Arthritis was corroding her joints and she was getting dizzy, putting her at risk of another fall. She had swollen knees and hands, and was finding it increasingly difficult to get out of bed and out of chairs.

Following Peter’s letter, his daughters tried to keep him and Pat as content as possible. They visited more often. They tried to work out ways of helping. They attempted to cheer up the pair with fine whisky and wines. Surely they wouldn’t go when there was another bottle of duty-free Laphroaig in the pantry, Kate thought. But her parents had other plans.

Anny, their second daughter, asked if they could wait for one last Christmas. But they couldn’t. Or wouldn’t.

They set a date. Peter said it was time and Pat agreed. They would enter the “big sleep” together on October 27, the day after Pat’s 87th birthday.

Anny got on a plane. When she arrived in Melbourne on October 21, she was shocked at how frail her parents looked. She would often find her father slumped in his chair. Her mother was struggling to move in the purposeful way she used to. Anny showed them a DVD of concerts she had performed with the Munich Radio Orchestra. But she could see that her parents had changed. They were tired. Even a bit bored, she thought.

On their final night together, the family shared a last supper of sorts. The sisters prepared a plate of cheeses, avocado and smoked salmon to eat with wine. Peter and Pat pecked at it. They didn’t seem very interested in food. Anny picked up their grandmother’s violin and played for her parents. They went to bed around 10pm.

The next morning, Peter and Pat got up early. They showered, dressed and made their bed. Peter had breakfast, a fried egg and coffee. Pat did not eat. She wanted to keep her stomach empty for what was to come.

The family sat in their backyard in the soft morning sun, enjoying the native garden that had flourished around their Robin Boyd-style home. Peter had designed the house himself in the 1960s.

“They were more cheerful than I had seen them since I arrived,” Anny said.

“They were just relaxed and ready to go.”

Everybody knew the plan. The sisters were to leave around noon. They felt they had no choice. Assisting, aiding or abetting a suicide carries a penalty of up to five years’ jail in Victoria. Their mother would have liked them to stay, but not at the risk of prosecution.

Pat did not want to die by herself, so she would take a lethal drug first. After leaving her in their bed, Peter would walk alone down the hall of their home and into the living room where they had shared so many hours. He would open the back door and trek one last time through his yard and into his shed where his equipment was set up.

In those final hours, everybody was calm. They discussed the need to lock the doors after the sisters left. People were always coming and going through the house. It would be a bad time for anyone to come knocking.

While Peter discussed the logistics, Pat mused about any final homilies she could offer her daughters before she left them. Peter joked that they had never listened anyway.

“It was all so normal,” says Kate. “I just started laughing at the surreality of it … and took out my phone to take some photos – something I never do.”

And then it was time.

Just before noon, the sisters embraced their mother and father and left. There were no tears.

They walked out of their family home and walked down to the cafe where Peter regularly sipped coffee during his “morning totters” with his friend Frank. They wandered on the beach where they had grown up, and waited.

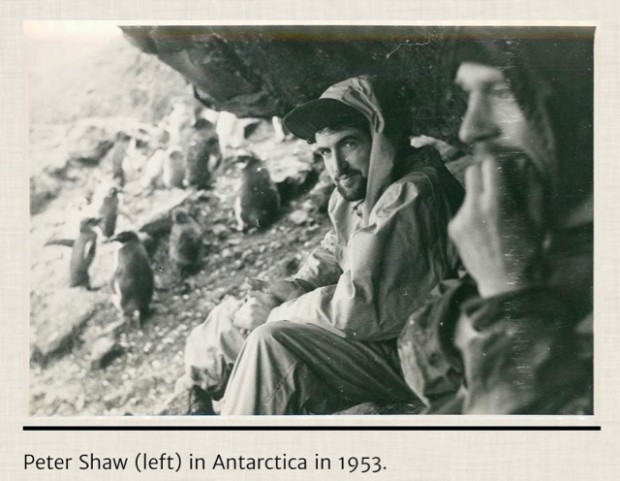

Somewhere in Antarctica, there is a mountain named after Peter Shaw. He conquered it in 1955 on a pioneering mission with the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions. The following year, he was awarded a Polar Medal for the mission and he was immortalised on a postage stamp. The trip had been tough. He and his companions had endured at least one terrifying storm that was so traumatic no one ever spoke about it again. They relied on candles for light and layers of wool for warmth. There were no fancy gadgets.

The year that Peter stuck an Australian flag in that peak was the same year he fell in love with his sweetheart.

Patricia was the “it girl” in their mountaineering club. Dazzling blue eyes and blonde hair. But Pat – or Patsy as she was sometimes called – was more comfortable in shorts and hiking boots than dresses and baby-doll heels. She was whip smart, too. Had plenty to say and knew what she was talking about. The first time Peter ever saw Pat, he later told the girls, he had turned to a friend at the club gathering and asked who she was. The attraction was mutual. They married when they were 27.

During the 1950s, Peter worked as a meteorologist for the Bureau of Meteorology while Pat, one of the first women to study biochemistry at the University of Melbourne, worked as a nutritionist. She took a break from it in 1957 to have her first daughter. But she never fancied herself a stay-at-home mum. After their next two girls arrived in 1959 and late 1960, Pat started teaching at Monash University where she became a lecturer in the medical faculty.

In the early 1960s, Peter read the weather for the ABC and Channel Seven – a small taste of fame. But he was no peacock. He was better known for his principles and dedication to the Professional Officers Association where he concentrated on winning fair pay and conditions for his peers. He was admired for his encyclopedic knowledge of meteorology, and for his ability to be direct and frank when something needed to be said.

An old colleague, Michael Hassett, recalls him flooring everybody at a meeting in the late ’70s about a controversial plan to collect data on Bureau of Meteorology employees. After several timid questions from the crowd, Peter stood up and said, “I don’t have a question, I want to deliver a tirade.”

“He lambasted the proposal as a thoroughly bad idea from start to finish and suggested it should be abandoned. Not long after that, it sunk without a trace,” Michael said.

They lived their lives well, and on their own terms.

Now their daughters waited on the beach. Their greatest fear was not that their beloved parents would die, but that they – or worse, one of them – would not. The Shaw sisters trusted their parents and had faith in their plan but they were still aware of the many things that could go wrong. What if the drug their mother had buried in her garden for fear of a police raid had lost its potency? What if one of them survived to be accused of killing the other?

Nobody knows precisely what happened in Peter and Pat’s last moments but when the sisters returned to the house, about 1.30pm, their mother was lying still on her back in bed. There was a note on the bench from their father in spidery handwriting. It said, in part: “Satisfactory for Pat and for me, eventually”.

They found their father in the shed, reclining in a chair. They checked for signs of life – or death. Heartbeat, pulse. First their mother. Then their father. Nothing.

There is no good way to lose your parents. When the three sisters returned to their parents’ house, they were orphans. The plan had worked and there was no sign of suffering. Peter and Pat had set out to end their lives in a meticulous, scientific fashion without any fuss, just as they had lived. And they had done it.

What happened next was unsettling, though. The sisters called their parents’ GP. They had expected him to be able to come promptly and quietly certify their deaths. But he was caught up with patients all afternoon. He told them the two deaths required a call to triple zero.

This was when the outside world started to push in. Within minutes of the call, paramedics arrived, lights flashing. The police were not far behind. Two people had died in a suicide pact and their three daughters were at their home. Suddenly, a very private decision had become a very public event.

Kate met the paramedics at the door. The medicos wanted to rush in. She stopped them to explain. Their parents had intended to die; they did not want to be resuscitated, she said. It took some discussion. Eventually the paramedics entered, attended the bodies and documented the deaths. They were respectful, say the daughters. The police were also sympathetic and supportive when they understood what had happened. But the homicide squad still had to be called in. The Shaw family home became a crime scene. The sisters were told to attend a police station to make statements. No charges have been laid.

To erase any doubts about their deaths, Peter and Pat had both written suicide notes. Each said they had died by their own hand, with no assistance or pressure from others. In a letter left with his solicitor and titled “To be opened after my death”, Peter had written that he was “sane, quite good-humoured, and not at all depressed”. He said he was making a rational decision.

“I am not religious, and I look forward calmly to a sleep from which I will not wake,” he said.

“I have had a good life, and prolonging it will not make it better.”

Pat wrote a note in her own cursive hand and tucked it into a notebook with the family’s “X’mas pud” recipe for her daughters. The note, written on cream paper, said she had no help from her family, whom she loved very much.

“I am of sound mind, with no hint of dementia or depression … Having seen my two sisters die in nursing homes, I have no wish to go that way,” the letter said.

“In case there should be any doubt, I declare that my death is by my own hand.”

Today the Shaw sisters are still coming to terms with the loss of both parents. They miss their wit and warmth. But they respect their choice and feel strongly that suicide can be rational. All three say their parents should not have had to risk prosecution to die together at the time of their choosing. Nor should they have had to be alone for the legal protection of their family.

“It shouldn’t be so difficult for rational people to make this decision,” Kate said. “Obviously, care has to be taken but assisted suicide should not be illegal.”

Anny and Kate, the two sisters who have been willing to talk publicly about what happened that day, have been honest with many people about their parents’ choice. Some have been awed. Most have been deeply supportive. But a couple have passed judgement. One friend suggested Peter and Pat had been selfish for leaving their daughters. Another acquaintance hinted to the daughters that they must not have offered enough support. Why would their parents leave them if they knew they would be cared for?

But Kate says anyone who suggests this does not understand the Shaws, a family of fiercely independent rationalists. Her parents never wanted to leave their home nor be cared for. Nor were they the types to sit around for another decade with rugs on their knees.

“To those people who say we don’t have the right to choose the time and manner of our departure, our mother and father said, ‘Well, we do and we did’,” she said.

“I love their defiance right to the end. But these were two extraordinary human beings.”