December 24, 2019

A design for death: meeting the bad boy of the euthanasia movement

The Economist 1843 Magazine, Mark Smith

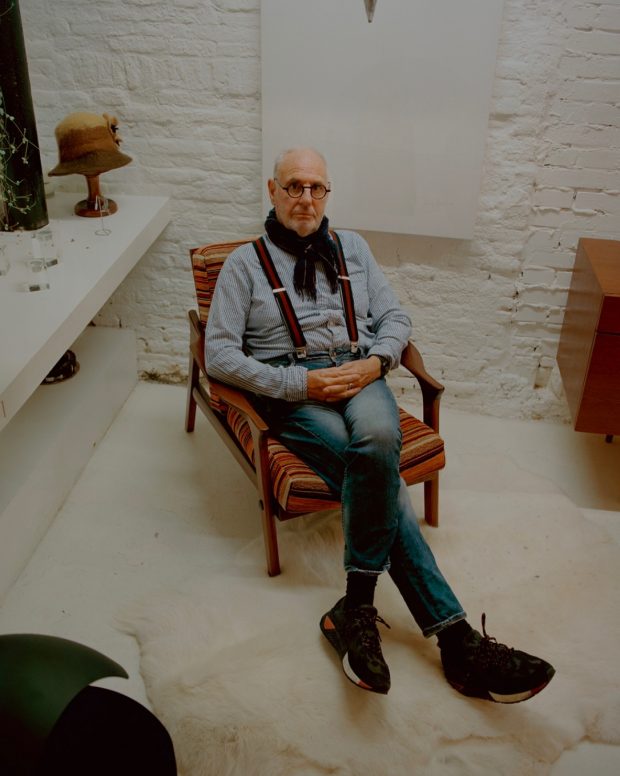

It’s a sunny autumn morning in the Jordaan, Amsterdam’s chocolate-boxiest district. Over tea in a modishly renovated maisonette, a voluble Australian 72 year-0ld wearing round glasses and fashionable denim is regaling me with his new-year plans, which involve “an elegant gas chamber” stationed at a secret location in Switzerland and “a happily dead body”.

My host’s name is Philip Nitschke and he’s invented a machine called Sarco. Short for sarcophagus, the slick, spaceship-like pod has a seat for one passenger en-route to the afterlife. It uses nitrogen to enact a pain-free, peaceful death from inert-gas asphyxiation at the touch of a button. With the help of his wife and colleague, the writer and lawyer Dr Fiona Stewart, Nitschke is ushering the death-on-demand movement towards a dramatic new milestone – and their enthusiasm is palpable.

“We’ve got a number of people lined up already, actually,” says Nitschke, whose unique CV (and previous occupation as a registered physician) has earned him the nickname “Dr Death”. The front-runner in the one-way journey to Switzerland is a New Zealander whom Nitschke has known for years. She’s not terminally ill, but is becoming increasingly disabled by macular degeneration – something she finds intolerable after a lifetime of reading for pleasure. “She’s also got an ideological, philosophical supportive commitment to the idea,” explains Nitschke. “She’s coming from a long way because she likes the concept and she sees it as the future.”

Whether that future is utopian or dystopian depends on your perspective. Nitschke has twice been nominated for Australian of the Year for his work with Exit International, the “end-of-life choices information and advocacy organisation” he founded in 1997; activities include the publication of The Peaceful Pill, a continuously updated directory of information on how to end it all. But over the past two decades, members of the medical, psychiatric and even the pro-voluntary euthanasia communities have come to reject his brand of increasingly strident – some say extreme – advocacy for what he terms “rational suicide”: an individual’s inalienable right to die in a manner of their choosing.

His one time ally, the former UN medical director Michael Irwin, has branded him “totally irresponsible” for telling people how to obtain drugs that could help them end their own lives. And in August 2019 the grieving daughter of a man who took his life after contact with Exit International denounced Nitschke, saying “the information you put out kills people who are not in a rational state of mind to make that decision.”

Nitschke says he doesn’t want “to make a load of money from it,” but there’s Silicon Valley swagger in his latest project’s ambition to disrupt the business of elective death through technology. The Sarco concept came to Nitschke while watching “Soylent Green”, a 1970s sci-fi movie in which Charlton Heston, disgusted by a world ravaged by global warming, seeks euthanasia in the serenity of a customised government clinic. It’s set in 2022. Eventually, Nitschke wants the 3D-printed Sarco to be accessible on demand to anyone, anywhere – a sort of cosmic Uber into the great beyond. But for now, he’s taking his invention to Switzerland because it’s the only jurisdiction worldwide in which, “so long as there’s no malicious purpose”, assistance in a suicide is not a crime.

Nitschke and Stewart are much jollier than you’d expect the right-to-die movement’s only power couple to be. They’re full of – well – joie de vivre and arch banter about everything from Brexit to the roadworks that have denuded the front of their home of a beloved creeper. “If it’s not dead, boy is it doing a bloody good impression of being dead,” observes Nitschke, correctly.

Stewart is at the kitchen table, processing applications from her laptop, and asking correspondents for proof of age. Officially, membership to Exit is restricted to the over 50s, and its members are mostly in jurisdictions where neither assisted suicide nor euthanasia are available – which is to say, most of the countries in the world. “I’m the door bitch,” she jokes.

Stewart had been a pro-choice advocate in Australia before meeting Nitschke at a festival of ideas in Brisbane in 2001. Later, she would be horrified by the state of his nascent organisation. “She said, ‘This is a mess – you’re not paying enough tax, your business is a shambles and it needs proper management.’” says Nitschke. “She turned the whole thing around. I can’t do much without her.”

One of those opposed to Sarco is Paul Biegler, adjunct research fellow at the Monash Bioethics Centre in Victoria. “You can make an argument that people have got a right to control the time of their death,” he tells me over Skype, later. “You could make an argument that rational suicide in the absence of a terminal illness is a defensible option for some people. But it really is a quantum leap to go from saying that people have a right to choose the time and nature of their dying to providing a mechanism for that to happen.”

A comprehensive assessment of worldwide data in 2016 showed that, in areas where euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide are legal, 0.3-4.6% of deaths result from them, with more than 70% of cases involving patients with cancer. The report described these numbers as an indication that despite growing legalisation the practice “remains rare”. The Netherlands’ relatively permissive law stipulates that to qualify for either procedure an applicant must be shown to be experiencing “unbearable suffering from which there is no prospect of recovery” with “no reasonable alternatives” available to end that suffering.

It has been criticised for not making a distinction between physical and mental distress, which could, in theory, justify euthanasia for psychiatric patients. Switzerland’s law is looser – foreigners can travel there and legally access physician-assisted suicide. The only two legal requirements a candidate is required to satisfy are the intention to end their life and soundness of mind. “The general approach [for the latter] has been to get a ticket of approval from a psychiatrist,” notes Nitschke.

The Sarco project bore fruit at the same time as subtle legal developments in Switzerland. Although there’s nothing in Swiss law to state that a person must be terminally ill to be eligible for assisted suicide, in practice, says Nitschke, “groups such as Dignitas have chosen to further medicalise the legislation,” he says, “because the only way they could get a doctor to prescribe [the lethal dose of the barbiturate] Nembutal was for the person to say they were sick.”

This, he thinks, is specious and evidence of the medical profession’s creeping paternalism, which he finds abhorrent. “[Doctors are] always there, setting themselves up as the gatekeepers when it comes to areas of human endeavour that they should have no role in – because when you medicalise something you’ve got to have a medical controller,” he says.

The great irony of Nitschke’s career, in his view, is that he seems to spend as much time “arguing with people on my own side” as he does weathering the rebukes of “the born again Christians.” He recalls being denounced by Dignity in Dying (in its former incarnation as the Voluntary Euthanasia Society) after he was detained, then released, by authorities at Heathrow airport on his way to host Exit workshops in the UK whilst carrying equipment for testing the safety of Nembutal, the barbiturate most often used for lethal injections, which terminally ill individuals were starting to obtain online from questionable sources.

“They came out and said I was a danger to the movement. I found that annoying but I suppose what we were seeing was a difference in philosophy. I was telling people: get your own drugs, test your own drugs, be in control; they were saying: change the law, convince the politicians…”

It’s undeniable that Nitschke’s campaigns have exhibited a certain PR-savvy pizzazz. He is the originator, no less, of the euthanasia flash mob, which took place to celebrate his 70th birthday and 20 years of Exit International (soundtrack: Bon Jovi’s “It’s My Life”, naturally). When he announced plans for Sarco, it was dismissed by some, says Nitschke, as “a stunt, or some virtual creation in someone’s mind that didn’t have any prospect of physical reality.”

I can attest that the machine exists, having had the singular experience of reclining on a prototype at Nitschke’s workshop on an industrial estate in Hillegom, South Holland, amidst the incongruous spring blaze of the tulip fields. Plus, scratch the surface of his provocative patter and there’s a person – a patient – lurking behind each of his convictions.

Even aged 18, Nitschke demonstrated a flair for taking the law into his own hands after thieves stole the radio from his car, which was parked outside a dance. The police told him it was too small an affair to pursue so Nitschke spent two Saturday nights hiding in the boot with a .22 caliber rifle waiting for the thief to return. They did, and Nitschke marched them to a telephone and called the police, who arrested the thief and retrieved the stolen transistor. “You should solve your own problems is how I’d put it,” says Nitschke.

Nitschke studied physics at the University of Adelaide before heading to the Northern Territory to work as an Aboriginal land-rights activist. Having studied for his medical degree with, he says, the intention of “curing himself of hypochondria,” in 1996 he became the first doctor in the world to administer a legal, lethal voluntary injection under the short-lived Rights of the Terminally Ill Act which, astonishingly, made the statute books in the Northern Territory by one vote.

“Suddenly we had a law which meant terminally ill people could legally seek help from a doctor to die,” he recalls. “And when a patient came to me who was eligible, because he was dying of prostate cancer, as much as I was passionate about his right to die, I didn’t want to be the one to do it, you know, so I built a machine that would downgrade euthanasia into assisted suicide. I would load it up and put the needle in the vein, all that stuff, but he was the one pressing the button.”

That patient’s name was Bob Dent and Nitschke’s invention, the Deliverance Machine – listed on the Wikipedia page for notable euthanasia devices in history and now on display in London’s Science Museum – lasted eight months and ended the lives of three more people before the law was overturned and assisting in a suicide became a serious crime again.

“The other important aspect of the Deliverance – and this certainly doesn’t apply to Sarco – was that it meant the user was able to die in his wife’s arms,” says Nitschke. “The machine didn’t take up much space so he was able to press the button, push the machine away and hold his wife,” his usually robust voice crackles. “I was on the other side of the room,” he says.

Initially, Nitschke ran Exit workshops exclusively for the terminally ill. His self-described “big, blinding road to Damascus change” came courtesy of a French academic from Perth named Lisette Nigot, whom Nitschke met in 1999 when she was 76. She had no desire to live to see 80, and repeatedly approached Nitschke asking for information about suicide drugs.

“I always said to her, that’s ridiculous: you’re not sick, go on a world cruise or write a book. And one day she said: ‘Mind your own business. I make this decision – you run around imposing your template on other people of what a life worth living is and dole out your information only to those people you think meet your criteria. You’re the worst example of insufferable medical paternalism I’ve ever met.’ I immediately crumpled and fell apart and agreed with her. It really affected me.”

There’s a photograph of Nigot – whose 2002 suicide-note declared Nitschke to be her inspiration – on the wall of the workshop in Hillegom.

Nitschke developed Sarco with the help of Haarlem-based industrial designer Alexander Bannink. “My original design looked more like a bathtub,” says Nitschke, “whereas Alexander really pushed the idea of making it resemble a vehicle, to give the sense of going somewhere.” Engaging suppliers for the project has been interesting. “When we first went to see a company down in Vlaardingen about building these strange aluminium tanks, I said to them, I’m building some sort of death machine, do you want one of your logos on the side of it?” They declined.

Sarco’s raison d’être, admits Nitschke, is aesthetic. It obviates what he calls “the yuck factor” inherent in other tools of “peaceful” suicide, such as the humble plastic bag and gas. “That’s just as efficient,” he says. “You can tell people over and over and over, as I do in my workshops, that it’s cheap, reliable, quick and legal, but they say, I don’t care if it’s a peaceful death, I do not like the look of it and I don’t want to be found like that.”

Sarco, meanwhile, is positively Instagrammable. A sleek conveyance that wouldn’t look out of place in a Tesla showroom, it consists of a detachable capsule – a coffin, essentially – mounted diagonally on a stand. Once inside, its user presses a button, prompting the release of nitrogen from a store-bought canister. “From a physiological point of view, it is peaceful,” says Nitschke. “It’s not the same as a rope around the neck, a pillow in the face or a head underwater – these are mechanical obstructions to breathing and they’re terrifying, let me tell you.”

Unlike previous Nitschke-devised death technologies, Sarco does not require the procurement or prescription of drugs. This is handy because Nitschke is no longer a doctor, having publicly burned his medical licence in 2015 following a dispute with the South Australian chapter of the Medical Board of Australia. It suspended Nitschke before offering to reinstate him providing he fulfil 26 criteria which included refraining from talking about euthanasia. Shortly afterwards, Nitschke and Stewart moved to the Netherlands on an entrepreneurial visa.

Then came the elective death in May 2018 of Nitschke’s friend, the 104-year-old botanist David Goodall, who refused to declare any serious condition beyond being “tired of life” but was nevertheless allowed to kill himself by lethal infusion at the Life Circle facility in Basel. “That set a precedent,” says Nitschke.

Nitschke and his lawyers began the process of setting up what he vaguely calls “an organisation” in Switzerland to facilitate the use of Sarco for those who want to end it all for whatever reason. For now, he’s keeping the specifics of the facility and its whereabouts close to his chest for fear of sabotage, but he says he’s been talking to amenable local psychiatrists – whose participation he’ll need because the “soundness of mind” criterion still stands – and is confident of success.

It’s late November – Black Friday, in fact – when I call Nitschke on his mobile for an update. He and Stewart are on the road with Sarco in tow, having retrieved a display model from a flooded Venice, where it has been on show at the Palazzo Michiel as part of the Venice design festival since May (pictured above). “It was bloody awful,” he says of the devastation in Venice. “Fortunately Sarco was on the palazzo’s first floor, but still it had to be carried by people wearing thigh-high waders, put on a barge and floated out of the place.”

I ask whether Nitschke is feeling nervous about a debut for which there can, after all, be no dress rehearsal. “There is a great deal of apprehension and nervousness,” he affirms, “and I can sense it building now as I watch the calendar days ticking down. I’m getting more and more anxious about it because I well and truly recognise that there’s a lot hinging on this for other people whose wishes are very important to me and, while I want things to run smoothly there’s always the possibility of some bizarre eventuality you can’t predict. But once I’ve got the comfort of seeing the successful initial uses of the machine I think I’m going to be very pleased indeed.”

He suspects the reaction against Sarco has been so strong because the whole ethos of the device “flies in the face of the current Western paradigm, which dictates that all human effort and endeavour should be directed towards living longer at all costs, and any death is perceived as some fundamental failure that must be conducted shamefully, privately and in secret.”

He thinks technology is affording us the opportunity to consider how the end of life might be reframed “as a cause for some celebration or at least a momentous event, as it has been regarded by other cultures and in times gone by”.

I ask the obvious question: what a successful death might look like in his own case. It would depend, he says, on the circumstances. “But I know what I don’t want. I don’t want to be stuffed full of tubes with doctors hovering over me, pleased with themselves for keeping my heart beating for another five minutes, eking out every last painful second. That, to me, is dystopia.”

Mark Smithis a freelance writer based in Amsterdam.